- Home

- C R Hallpike

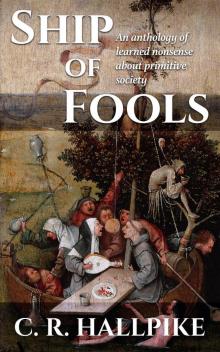

Ship of Fools

Ship of Fools Read online

Ship of Fools

An anthology of learned nonsense

about primitive human societies

C. R. Hallpike

Copyright

Ship of Fools: An anthology of learned nonsense about primitive human societies

C. R. Hallpike

Castalia House

Kouvola, Finland

www.castaliahouse.com

This book or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission of the publisher, except as provided by Finnish copyright law.

Copyright © 2018 by C. R. Hallpike

All rights reserved

Version: 002

Contents

Preface

Chapter I: Talking nonsense about early Man

Chapter II: A response to Swearing is Good for You. The amazing science of bad language, by Emma Byrne.

Chapter III: Review of Yuval Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

Chapter IV: René Girard’s world of fantasy

Chapter V: The Man-Eating Myth reconsidered

Chapter VI: So all languages aren’t equally complex after all

Chapter VII: Some afterthoughts

References

The crew are all quarrelling with each other about how to navigate the ship, each thinking he ought to be at the helm; they know no navigation and cannot say that anyone ever taught it them, or that they spent any time studying it; indeed they say it can’t be taught and are ready to murder anyone who says it can. They spend all their time milling round the captain and trying to get him to give them the wheel.… They have no idea that the true navigator must study the seasons of the year, the sky, the stars, the winds and other professional subjects, if he is to be really fit to control a ship.

—Plato, The Republic , Bk. VI, Tr. H.D.P. Lee

Preface

I spent my first ten or so years as an anthropologist either living with mountain tribes in Ethiopia and Papua New Guinea or writing up my research for publication. These more primitive types of society are small-scale, face-to-face, without writing, money, or the state, organized on the basis of kinship, age, and gender, and with subsistence economies. As such they are very different from our own modern industrialised societies and it takes a good deal of study to understand how they work. But since all our ancestors used to live like this, understanding them is essential to understanding the human race itself, especially when speculating about our prehistoric ancestors in East Africa. Unfortunately a variety of journalists and science writers, historians, linguists, biologists, and especially evolutionary psychologists think they are qualified to write about primitive societies without knowing much about them, or, even worse, think that a political agenda justifies them in falsifying the record. The result in many cases has resembled a Ship of Fools, True Believers in some pet ideology like extreme neo-Darwinism, or social justice, or some will o’ the wisp of their own imaginations, and many of their speculations have about as much scientific credibility as The Flintstones. So the various critical studies in this little book are offered as a sort of bouquet or anthology of nonsense about primitive man, and I only hope my readers derive as much entertainment from them as I have had in writing them.

C.R.H.

Shipton Moyne

Gloucestershire

August 2018

Chapter I: Talking nonsense about early Man

1. What primitive societies are actually like

Before joining the Ship of Fools I thought it might be useful if I began with a rough guide to what primitive societies are like.

The most powerful impact of primitive society on the anthropologist is what I can only call the sheer immediacy and intimacy of the physical world, even in comparison with rural life in Europe or North America. In our WEIRD culture (Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic) ¹ , we experience the physical world to a great extent indirectly through our technology. So instead of walking we encounter the countryside through our cars, we talk to family, friends and neighbours over the telephone, and when we want water we turn on a tap, which brings it from some fairly distant part of the country by a huge system of reservoirs, pumping stations and pipes. In primitive societies, however, someone, almost invariably a woman, has to go and fetch it themselves from a water-hole, or stream, or well, in a bamboo or gourd container, or perhaps in a clay pot and carry it wearily home, sometimes several times a day. (Even in our own society just within living memory the village women would congregate at the pump or well on the green to get their water.)

In the primitive world everything is made by the people themselves, not out of metals and plastic in remote factories in other countries but out of familiar local materials—wood, plants to use for thatching, thread, baskets, gourd or bamboo containers, stones for building and tools, and animal products like hide, sinew, and bone. The primitive world is also very small and human-sized. There are no great cities or gigantic multi-storey concrete buildings, just villages of small huts thatched with grass or palm leaves, the roof held up by wooden posts and maybe some wattle and daub to keep the draughts out, and with no furniture like tables, chairs and beds, let alone anything comfortable like sofas and armchairs. Just the bare ground to sleep on, except for a cowskin or some leaves, and nothing to sit on either, except perhaps for some stones or a piece of wood, and with no tables to put anything on. People grow the food they eat, probably very limited in variety, in the gardens and fields they own, and bring it home, usually on the women’s backs, though in some societies there may be donkeys or other beasts of burden.

So life is extremely hard, and the food is usually dreadful. Members of our intelligentsia who chatter about the joys of this kind of life would probably have to be medically evacuated after a few weeks if they actually had to live with them under their traditional conditions of existence. The basic Konso meal, for example, mainly consisted of boiled sorghum dough and tree leaves, eaten three times a day, and sorghum is an unappetising cereal that is regarded by northern Ethiopians as fit only for cattle. Chaqa , the beer made from it, is a sour alcoholic grain soup, usually served hot, which compares unfavourably with Ethiopian tej (honey wine) or beer made from barley. While Konso coffee is excellent, traditionally it was not drunk but the beans were roasted and eaten on ritual occasions, and honey was not used to make a drink either. Milk, if available, is drunk only by children, and butter, which is very expensive, is used more as a cosmetic than as an item of diet. Meat, to be sure, is sold in the markets as a luxury, but there is a notable absence in Konso of the spices which elsewhere in Ethiopia are used to produce a range of appetising dishes. Chickens were kept in the traditional society, but only for their feathers, since it was forbidden to eat any kinds of bird or their eggs.

The Tauade of Papua New Guinea grew sweet-potatoes, which are a good deal tastier than sorghum, and much easier to prepare, as well as yams and taro, with pork and smoked pandanus nuts as treats. But since meat in farming societies is a luxury, people are none too fussy about its quality. Garide, my Konso cook, and I had been up to the market one day to buy some meat and had brought it back in a plastic bag. In the hot season in Africa this is not a good idea, and when we came to open it some hours later the stench was appalling. A man happened to be passing the doorway of my house, however, and was very keen to buy it for the small sum we were asking and snapped up his bargain with alacrity. In Papua New Guinea the people are even less fastidious about their pork when it is stinking, even cutting it up under water when the smell is too bad. And yes, sometimes they died from it. Biologists often tell us that we are protected by the vomiting reflex from eating meat

that has begun to smell as it goes bad, but no one seems to have told primitive peoples about this.

While the Konso had cattle, as well as sheep and goats, they couldn’t use them to plough, as their fields consisted of narrow stone-built terraces which made ploughing impossible. For tilling and weeding they had to use hoes, and everything they made or did was based on grueling human labour under the African sun with nothing in the way of machines, except the loom for weaving. The Tauade were even simpler farmers with no traditional knowledge of metal, whose animals were simply pigs and dogs; they could only till the ground with wooden sticks, did not use manure like the Konso, and so had to make fresh gardens every three years or so by cutting down the bush with stone tools and burning it.

The anthropologist must simply get used to the public slaughter of animals. For example, a few days after I arrived in Buso (the Konso village where I first lived), a goat was sacrificed outside my front door. At the moment of sacrifice the goat was held up in the air: “[T]here, held up by his four legs, he stayed for about thirty seconds, and then had a spear pushed into his chest. He looked round in a bewildered way, and gave a dreadful cry, which was echoed joyfully by the men and boys. Some more spears were thrust into him and he gave some more horrible cries. They finished him off on the ground with knives, pretty crudely, with much gurgling and shrieking” (2008: 364-5). The killing of pigs among the Tauade was also a formal occasion, though not a sacrifice, because there was a taboo against killing one’s own pigs: “They are like our own children”, I was told, so someone else had to do it for them. This led to ceremonial killings at which speeches were made, followed by the killing of the pigs which was done by beating them over the head with the equivalent of baseball bats as they lay on the ground. The thuds of the blows, the shrieks of the dying animals, and the blood streaming from their nostrils being lapped up by the village dogs took some getting used to. At my first pig-killing somebody varied the procedure by shooting one of the pigs with a 12-bore shotgun in the face, while another large boar was put on the fire (to singe off the bristles) while still alive and screaming horribly. (They did, however, agree to my request to club it more thoroughly and put it out of its misery.)

Inside the Konso sleeping huts there were giant cockroaches, scorpions, poisonous centipedes, rats, and the occasional cobra. People generally slept on the ground on cow-skins, and the only wooden bed-stead I encountered was infested with bed-bugs. To go to the lavatory they went to screened-off places on the edge of the towns, and when the faeces had dried they were mixed with animal manure to be spread on the terraces. Not surprisingly human manure also attracted the flies, which then settled on the children’s eyes and gave them severe conjunctivitis. The mothers would bring them to me with their eyelids gummed together with pus, and when I had finally washed them sufficiently to get the eyes open they would usually run with blood, so severe was the infection. The children were also particularly troubled with head-lice and often had their heads shaved as a result. While the Konso had some traditional remedies for minor ailments, they were essentially defenceless against serious illness and had to trust to their natural resilience. The Tauade were in a similar situation, but living in much smaller settlements at a higher altitude and with more rainfall they were less subject to diseases.

Again, we take light so much for granted now, in our electric civilisation, but going to live in a primitive society it is a real shock, after the very brief tropical twilight, to encounter the profound darkness that can fall after the sun has gone down, especially when there is no moon. Without candles or lamps, people only had light from fires, or perhaps a burning brand in emergencies. I well remember how demoralising it was when my pressure lantern would suddenly go out and the brilliant, comforting light all around me would vanish and leave me with the dim glow of my hurricane lamp, and there was no way of investigating those disturbing sounds—is that a snake, or just rats? Konso homesteads had lots of stone walls, and one could put one’s hand in the dark on a cobra looking for rats. The night was filled with threatening supernatural presences as well, and my cook, Garide, told me that he hated walking home to his village every night when he left me because the path took him through a sacred grove where he could hear the ghosts talking.

Where water is scarce and is arduous to fetch, drinking and cooking take priority over hygiene by a wide margin, and I never saw the Konso (or the Tauade, for that matter) wash their hands before eating. The Konso women liked to put butter in their hair to make it shine, and especially at dances it would run down their chests in black rivulets. They wore leather caps on their buttered hair, and their skirts were also of leather, which was very hard-wearing but could not be cleaned, and in any case they had no soap or detergents to do so, even for their cotton blankets and the men’s shorts.

Most primitive peoples live in the tropics, which means that they don’t actually need to wear any clothes at all, but for reasons of sexual modesty most wear some sort of genital covering, particularly women. This is quite easy to make out of leaves or something similar, but garments for the rest of the body are quite another thing. Konso women wore rather elaborate leather skirts, even as little girls in their mother’s arms, because they had a strong taboo against exposing the female genitals, but bare breasts were a different matter and before the arrival of European clothes Konso women were all bare-breasted, like those of a vast number of other cultures. They were more relaxed about male nudity, and while men in my time wore simple shorts, it was said that in the past they had worked naked in the fields. Large garments to cover the body, however, rather than just the genital area, are extremely difficult to produce unless they are made from skins. The Konso men in particular wore large cotton blankets, like a toga, and these required professional weavers with looms, and many people to spin the large amounts of thread required. But larger garments of this size are generally worn for purely social reasons, such as to convey dignity of appearance, rank, occupation, and so forth. So it is only in modern times when European-style garments have become available that they have been taken up in primitive society. The Tauade apparently adopted European dress not because either the Catholic Mission or the government encouraged them to do so but because they hoped that by looking like the white man they would also somehow become rich. Since the end of the nineteenth century the Konso have been governed by the Amhara, who are a literate and sophisticated people, and who very much disapprove of the bare breasts of Konso women. It seems that this pressure, together with a fashionable appetite for modern dress, have been the major factors behind the adoption of clothes by the Konso.

In primitive societies unmarried adults, unless their spouse has died, are very uncommon, because marriage is an economic and social necessity. Some people may have a romantic image of primitive society as beautiful scantily-dressed girls with flowers in their hair making love with all and sundry. There was some truth in this as the early navigators discovered in Polynesia, where there was plenty of water for bathing, and a luxuriant and undemanding climate. Away from the beaches, however, the vast majority of primitive societies are very far from being erotic paradises, which need cleanliness and leisure. Water may be too scarce for much in the way of washing, so that people are pretty dusty, dirty, and sweaty, and what clothes they have will be fairly stinky, and the women especially have to work very hard. While some societies like the Tauade were sexually promiscuous, others like the Konso were not, and adultery was severely punished. In primitive society there is generally no accepted idea of romantic love, though no doubt some people may feel it. The individualistic image of “mates” freely choosing one another simply on the basis of some estimate of each other’s fecundity, which evolutionary biologists assume to be normal, is also quite unrealistic. Marriage in primitive society is very much not a matter of romantic love, or even of individual choice, and women in particular generally have to marry in accordance with custom and the wishes of their kin. I never saw married couples of the opposite sex kissing each ot

her, or displaying other signs of physical affection either among the Konso or the Tauade, and I can only recall once seeing a Konso boy with his arm round a girl’s neck.

The lack of clothing obviously makes the naked body much more obvious than it is in our society—the bare breasts of the Konso women being a case in point. So where we might use clothes to make social statements, in primitive societies people tend to do things to their bodies instead, like putting bones through their noses, long gourds over their penises, wearing paints, scarifying their faces, cutting off finger joints in mourning, or wearing things such as bells on the ankles of unmarried girls, or a special shell on the forehead by a man to indicate he has killed someone. Taking body trophies of enemies killed in warfare like heads or genitals is also common, and the eating of enemies killed in battle used to occur in many societies.

Birth, sickness and death are the commonplaces of daily life that everyone has to deal with, not hidden neatly away in professional establishments like hospitals, doctors’ surgeries, or funeral parlours. It used to be Tauade practice in Papua New Guinea to keep the bodies of Big Men in elevated baskets, tseetsi , to rot. These were inside the hamlets, and according to my informants the stench was appalling, with maggots from the corpse crawling over people as they slept. When the corpse had rotted the bones were collected and washed, then put in string bags. These were brought out at major dances and given to the guests to dance with as a form of honouring the dead. It was also Tauade custom for women to cut off one of their finger-joints in mourning for husband or child, and I saw a number of old women missing the ends of their fingers; in earlier years they also used to wear body parts of the deceased. “A recently bereaved widow had an arm bone, several rib bones and the complete hand of the late departed hanging on a string around her neck. She did not appear to mind the offensive odour”, as a patrol officer wrote in 1945. When I finally left, Amo Lume, my main informant, gave me his grandfather’s skull, and a thighbone as leaving presents, and they are still on my desk. As one might expect, the Tauade were totally at ease with the remnants of the dead, and I remember Amo one day finding a bit of pelvis in my garden: “Oh, that’ll be old So-and-so”, he remarked, tossing it over his shoulder. The Konso of Ethiopia, however, were the exact opposite, and had a complete horror of death. As soon as someone died the family had to carry the body out to their fields wrapped in a cowskin, while the men of the ward got together to dig the grave so that the deceased was safely underground before the end of the day. They were particularly careful to beat the earth down hard to prevent the smell escaping and attracting hyenas.

Ship of Fools

Ship of Fools