- Home

- C R Hallpike

Ship of Fools Page 2

Ship of Fools Read online

Page 2

The Tauade were happy to admit that they had been cannibals before the Australian administration had come, but they apparently did not go in for it in any elaborate way like the Fijians, for example. Accounts of battles would mention from time to time that allies in battles had been given a few bodies to eat, but they seem to have enjoyed mutilating them to upset their relatives when they found them. The Konso, needless to say, were appalled by the idea of cannibalism, but they did mutilate their dead enemies in battle by castrating them. I discovered this when I was attending a ceremony in the home of a friend, who had just sacrificed a ram to bless his lineage. He took a small piece of the animal’s hide, cut a slit in it, and put it on his wrist, telling me as he did so that this is what the Konso used to do with the penises of men they had killed in battle. It is interesting that a castrated man could not be buried on his own land in the normal way, possibly because he would bring sterility to it.

Living as we do mainly in large cities, ours are essentially societies of strangers. Even people in villages are always moving from place to place, primarily in relation to where their jobs take them. But in primitive societies people stay in the same place for generations so everyone basically knows everyone else, and not just as individuals, but as members of families and lineages and clans, who their fathers and grandfathers were, who they married, who their children are and where they live. They know who are the respected and the despised, those with a bad reputation for dishonesty or laziness or being quarrelsome, and the experts and the leaders, the wise heads and the moderators in disputes who make important contributions to the welfare of the group. Our lives are based on the nuclear family, and beyond this blood relationships rapidly fade away, but in primitive societies kinship is a central feature of their lives, and the basis of large groups, not just of isolated families, because people descended from a common ancestor form lineages and clans which are important sources of help in people’s daily lives.

It might be thought that members of primitive societies, being illiterate and uneducated, would behave in an uncouth and boorish manner like some of the working class in Western society, but this is quite untrue. The Konso had strict norms of behaviour, enforced by public opinion, while among the Tauade even what we would consider minor insults and slights could result in violent revenge, so people were extremely careful to speak and behave politely. I was interested, however, to see that neither the Konso nor the Tauade said “please” or “thank you”, possibly because when constantly interacting with people one knows one takes these exchanges for granted without the need for any special acknowledgment. But I had always assumed that greetings and farewells were human universals, and the Konso certainly used many of these—“Friend!”, “Peace today!”, “Sleep well!”, and so on, but much to my surprise the Tauade had none of them. No one said anything at all when meeting someone else for the first time in the day, and people would join a group in mutual silence. When leaving a man might possibly say “I’m leaving now”, but would often go without saying anything. I never ceased to be disconcerted when in the evening I was lighting my stove in my house and talking to someone who was outside on the veranda, and then look up to find that he had silently disappeared into the night.

We live in a market economy and have to earn money to buy our food, and need jobs, such as bus-drivers, doctors, civil-servants, firemen, shop-keepers, lawyers, and so on, all of whom have very different life experiences and also status particularly as employers and employees. But in primitive society people produce their own food and so do not need to work for anyone else by selling their labour for money, and their experience of life is far more homogeneous than with us. They simply till their land to grow their crops, and maintain their cattle, sheep, and goats, or their pigs, and killing and eating these is traditionally bound up with social ceremonies, which may involve religious sacrifice, or elaborate exchanges of meat at formal feasts. The only occupations resembling the jobs of our society are specialist craftspeople such as smiths, weavers, and potters, if they exist, but the Tauade didn’t even have these, and women knitting string-bags, and in the old days a few men in certain locations making stone tools were the only crafts.

So, in primitive society people’s identity is not tied up with their job as it is with us but with which social groups they belong to: their clan and lineage, the hamlet or village where they live, their age-grade, whether they are an eldest or a younger son, and especially their gender. There may be marked differences of social status, based on gender, age, being an eldest or younger son, and descent, as among the Konso, or from being a dominant and eloquent man with the ability to organise feasts and dances, as among the Tauade. But the fact that there was no money, and that people could not buy or sell their labour, meant that status was the basis of such wealth differences as there were, not, as with us, that wealth in money could be the basis of social importance. In any case, the poverty of material possessions meant that there could be nothing like the huge disparities of material wealth, especially in houses and possessions, that are basic to status differences in our society.

Among advanced farmers like the Konso there may be markets where people can buy necessities like tools, pots, and clothes, but even here money, recently introduced, plays very little part in daily life. Among the Tauade even markets did not exist, although traditionally men in some villages made stone tools, while the men generally made their own spears and bows and arrows, and the women knitted string bags to carry the produce home from their gardens.

One of the reasons that we meet so many strangers is that it is so easy for us to get about by all the various means of transportation that are available, and communicate by telephone and letter. But in primitive societies people can only communicate by talking face-to-face, and the only way of getting about, unless there are boats, is on foot along narrow paths, although people are not deterred by mountainous terrain. In Papua New Guinea I lived at around 7000 feet, and my neighbours would think nothing of going down several thousand feet, across the river at the bottom, and up the other side of the valley to take some trivial gift to a friend in a hamlet there.

It is very strange to live among people who don’t measure anything. The Tauade were an extreme case of this, as they had no number words beyond “single” and “pair”, and they had no means of reckoning time either, beyond a word, lariata , for “day”. They had no weeks, no months, and no years, and no means of counting them even if they had, so it was impossible to ask them even simple questions like “How long have you been living in this village?”, for example. If they wanted to explain when something had happened it would be in relation to some other event, such as “When my father planted those pandanus trees”, or “After the Mission came to Kerau”. It is perfectly possible, however, to grow crops without any calendar but simply from one’s knowledge of the seasons and the weather patterns, and the flowering of different plants. Nor did the Tauade ever try to measure size, or weight, or distance, and this was true of the Konso as well, although they had a well-developed counting system, and the same sorts of words as us like week and month for time-reckoning. When it comes to something like house-building the materials are cut by eye and in relation to the human body, not in our manner of blueprints and standard dimensions.

There is, of course, no writing of any kind, which means that the people have no historical records, and all human relations have to be face-to-face between real people: just as there is very little in the way of transport there is no form of writing or letters and other types of communication, least of all the variety of electronic communication we have. Since there are no newspapers all gossip and news, especially from outside the vicinity, is by word of mouth, as are all the traditions and collective memories of the society.

Without writing there is no call for any formal schooling—children learn all they need by participating in adult life as they become capable of doing so. In our society, however, school is where children get used to being questioned by their tea

chers about what they know, or why they think something is true. They are also encouraged to question what they are taught and to develop critical thinking and the ability to reason for themselves. This is all very well where there is literacy and institutions of higher learning, and jobs for engineers, computer-programmers, and professors, but it makes little sense in small non-literate societies with subsistence economies. There “The good child is the obedient child—smartness or brightness by itself is not a highly valued characteristic… wisdom is contrasted with ‘cleverness’, and wisdom includes good judgement, ability to control people and to keep them at peace, and skill in using speech” ² . And very sensible, too, one would say, in the context of primitive life. But our emphasis on self-conscious critical thinking and reasoning is one of the foundations of a basic aspect of our culture, which is the huge amount of reflection we engage in about our own thoughts and beliefs and states of mind, and those of other people. But in primitive society this aspect of life, which we can call “reflexive thinking”, is largely missing, and it is what people do that matters. In the same way they don’t discuss how their own society works and why it is like it is. I once had a conversation with a young man who had had several years at the Mission school, in which I said that the warriors and the elders each had their own kind of work to do in order for the age-system as a whole to work, and he found it very difficult to think along these lines because people are not used to thinking about the age-system as a working whole; they only know what they as individuals are supposed to do within it.

Again, unlike our society, where churches, scriptures, and formal religious institutions are clearly distinct from what we call “social” institutions like banks and trades unions, in primitive society these merge together, and there is no clear distinction between religion and society. So clans in tribal society are not just social institutions but are often thought of as having a close, “totemic” relationship with species of birds, animals and plants, and their founders and heads are seen as endowed with sacred powers. When I asked the Konso why they had adopted an extremely complicated age-grading system the standard reply was that “It makes the crops grow”, by which they meant that when there was harmony in society, Waqa the Sky God would send rain.

Religious rituals are basically public magic for health and prosperity of the community, with no concern with beliefs or individual salvation. Members of primitive societies assume they can interact by rituals, words, and actions with the physical world as if it were part of their own social world: they are not focused on a Heavenly world quite different from the world of ordinary experience. And what they want is not individual salvation—they have little interest in the life of the next world, and no idea of Heaven and Hell—but rain, good harvests, children, and good health, with possibly victory in battle against their enemies.

So to understand primitive society we have to think ourselves back from the urban to the rural, where everything is hand-made of local materials, not made by machines in far-away factories, from huge populations to fairly tiny ones, from societies of strangers to societies where everyone more or less knows everyone else as kin or neighbours, from literacy to complete absence of writing, from relationships dominated by money to relationships where the very idea of money is non-existent, where people are not organized on the basis of a huge range of different jobs, but of kinship, age, and gender which can also be mingled with the sacred so that the symbolic meaning of institutions often takes on profound importance.

2. Talking nonsense about primitive Man

Those who have no idea about any of this and want to speculate about early man or human nature in general simply assume that the lives of primitive peoples are basically like ours. For example, someone (Curtis 2013) has recently proposed that “The first, and most ancient function of manners is to solve the problem of how to be social without getting sick [from other people’s germs].” The picture of life in the background of this theory is obviously something like modern London, of dense crowds packed into buses and the Tube and breathing each other’s germs, shaking hands and kissing, using public lavatories, picking up things other people have handled in shops, and so on. Hunter-gatherer life, by contrast is very healthy: very small populations that cannot support epidemic diseases like measles and small-pox; no domestic animals, especially birds, from which humans can catch a whole range of infections; no clothes or houses which are notorious breeding grounds for a variety of parasites and their diseases; poor communications with other groups and their diseases; and a life in the sun and open air which are powerful antiseptics. If there was a “first and most ancient function of manners” it would actually have been to reduce social friction among small groups of people like this who have to live and get along with one another, not to avoid the largely imaginary dangers from communicable diseases.

Carrier and Morgan (2014) claim that men’s faces and jaws are more robust than women’s because for millions of years men have engaged in fist fights just like pub brawls in our society. First of all, in order for natural selection to have produced this result fist fights would have had to be lethal, and we know from bare-knuckle boxing in modern times that they aren’t. (Well-known instances of men being killed by a single punch are not the result of the punch but of falling and hitting their heads.) Indeed, where boxing is a social custom it is typically intended as a non-lethal form of competition, like wrestling. On the other hand, we know from anthropological studies that when hunter-gatherers (and everyone else) intend serious harm to one another they typically use weapons like clubs, spears, or rocks because they are so much more effective than trying to use one’s bare hands, which usually ends up in ineffectual scuffling unless people have been trained in martial arts.

Sex at Dawn (Ryan and Jetha 2010), by a psychologist and his wife, has been extremely well received by the general public. It claims that until 10,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers lived in communities where there was no such thing as marriage, but simply a sexual free-for-all. (They shared everything else, so why not each other?) Then, with the beginning of farming, there also came private property, and this meant that men started to worry about identifying heirs to whom they could pass on their land. This, in turn, produced monogamy and the regulation of our sexual impulses. First of all, it is generally accepted by physical anthropologists that pair-bonding is a key feature of human behavior which separates our species from all other primates, and must go back at least to Homo erectus . The elimination of female estrus allowed frequent sexual activity that cemented pair-bonding, and also “reduced the potential for [male] competition and safeguarded the alliances of hunter males” (Wilson 2004: 140-41). Secondly, if their theory were true we would expect to find a sexual free-for-all among existing hunter-gatherers, but marriage is actually a well-attested institution among them—primitive sexual free-for-alls are actually a Victorian myth. And thirdly, farming itself does not normally produce private property, but rather the communal rights of kin-groups over their land, and monogamy, at least as a norm, is far less frequent than polygamy. So, rather a disappointment for the polyamorists the book was intended to encourage.

But evolutionary psychologists have probably produced more fanciful theories about early Man than anyone else, and the rest of this chapter will be devoted to them.

(a) The first clothing

It is, of course, true that if we had retained the hairy coats of our primate ancestors we would not need clothes, and we are highly unusual among mammals in lacking effective body hair. Pagel and Bodmer (2003) have proposed that the selective advantage for hairlessness was that it provided freedom from parasites:

What features of early hominid evolution make hairlessness a plausible response to the toll exacted by parasites? Humans most likely evolved in Africa … where biting flies and other ectoparasites are found in abundance. Early humans probably lived in close quarters in hunter-gatherer social groups in which rates of ectoparasite transmission were high. Precisely when humans or their homin

id ancestors evolved hairlessness must remain a matter of speculation. What we can say is that having fire and the intelligence to produce clothes and shelter, early humans (and possibly even earlier hominids—Homo erectus may have had fire) were well equipped to evolve hairlessness as a means of reducing ectoparasitic loads, while avoiding the costs of exposure to sun, cold and rain. Ectoparasites can and do infest clothing, but clothes, unlike fur, can be changed and cleaned.… We suggest, then, that a set of cultural adaptations unique to humans made hairlessness a flexible and advantageous naturally selected adaptation. (2003: 118)

They then go on to argue that reduced amounts of body hair may further have been sexually selected for “by virtue of advertising reduced ectoparasitic loads”, and so being a desirable trait in a mate (ibid., 118). In fact we haven’t the slightest idea what the sexual preferences of Homo erectus might have been a million or so years ago, and for all we know the search for lice and fleas in each other’s hairy coats might have been erotically stimulating ³ . Leaving these speculations on one side, then, we can ask instead if Homo erectus might have worn clothing.

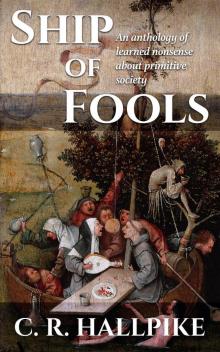

Ship of Fools

Ship of Fools