- Home

- C R Hallpike

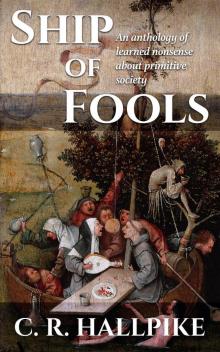

Ship of Fools Page 4

Ship of Fools Read online

Page 4

In conclusion, I would like to return briefly to this notion that the key threat to co-operation in human groups is the freeloading outsider. As I have pointed out again and again, in so far as freeloading is possible at all in such societies it only leads to contempt and low status for those concerned. The Tauade nevertheless did have very major problems with co-operation, but not because they were infiltrated by freeloading outsiders: if, for example, one asked them why they lived in small hamlets instead of big villages, the standard response was “It is because of our fathers”, in other words, festering internal grievances handed down over generations of people who knew each other well. The level of violence and homicide was actually greater within local groups than between them (Hallpike 1977: 119); the level of violence was greater between adjacent groups on the same side of a river valley (and who interacted frequently), than between groups separated by a river (and who interacted less often); and in the settlement of the Aibala valley it seems clear that a clan who claimed a certain territory first was very ready to invite groups of strangers to come and live there too since this increase of population was both militarily and ceremonially advantageous. The Konso clan and age systems were also designed to be able to assimilate strangers. Strangers, in other words, are not the problem because numbers are generally advantageous; if strangers start to be resented it is because they are thought to be putting too much pressure on scarce resources, not because they are thought to be cheats. It is the people one already knows and dislikes for one reason or another that are always the threat to social cohesion in one way or another.

(d) The evolution of religion

Evolutionary psychologists have always been fascinated by religion, and discussion of it usually begins something like this: “The propensity for religious belief may be innate because it is found in societies around the world. Innate behaviours are shaped by natural selection because they confer some advantage in the struggle for survival. But if religion is innate, what could that advantage have been?” (Wade 2007: 164).

“Religion” is not, in fact, some simple disposition that could possibly be either innate or learned. It is a highly complex phenomenon both psychologically and culturally, and there are major differences between the forms of religion found in primitive societies and the world religions with which we are familiar, as I have described in detail elsewhere (Hallpike 1977: 254-74; 2008a: 266-87; 2008b: 288-388; 2016: 62-88). But studying all these ethnographic facts is time-consuming and boring, and it is much more fun to assume that we all know what we mean by “religion”—something like “faith in spiritual beings”—and get on with constructing imaginative explanations about how it must have been adaptive for early man.

“No one”, continues Wade, “can describe with certainty the specific needs of hunter-gatherer societies that religion evolved to satisfy. But a strong possibility is that religion co-evolved with language, because language can be used to deceive, and religion is a safeguard against deception. Religion began as a mechanism for a community [wait for it!] to exclude those who could not be trusted ” [my emphasis] (ibid., 164). And how exactly is this supposed to have worked? The answer is apparently the basic vulnerability of all societies to those freeloaders who are always poised like vultures to take advantage of the system. “Unless freeloaders can be curbed, a society may disintegrate, since membership loses its advantages. With the advent of language, freeloaders gained a great weapon, the power to deceive. Religion could have evolved as a means of defense against freeloading. Those who committed themselves in public ritual to the sacred truth were armed against the lie by knowing that they could trust one another” (ibid., 165).

Now since ritual, myth, and symbolism are fundamental elements of religion in all societies, it is indeed perfectly true that, as embodiments of meaning, they all need some form of linguistic expression in order to be shared in a common culture. For example, the celebrated Hohlenstein-Stadel carving of the Lion Man, a standing male figure with a lion’s head, has been dated to 40,000 years BP, and it has been estimated that it took about 400 hours to carve (Cook 2013: 33). It seems inconceivable that anyone could have done this unless he could also have given some explanation of what he was doing to his companions that they would have understood, and this would have obviously required a reasonably well-developed language.

To this extent Wade is therefore quite correct to claim that “religion” could not have developed without language, but participation in religious ritual has nothing whatever to do with commitment to truth or security against lying. The Konso believed that Waqa, the Sky God, sent rain, indeed that he almost was rain: Waqa irobini , “Waqa is raining” was a very common phrase I heard whenever rain fell. He was also believed to withhold rain from villages where there was too much quarrelling, and could strike dead those who lied under a sacred oath. But a crucial difference between the Konso and ourselves is that we are fundamentally aware of the possibility of unbelief , of the denial of anything beyond the purely material, so that the assertion of belief in God as true in our society is not like the belief of the Konso in Waqa. In their culture there is no real awareness of the possibility of not believing in Waqa, and his reality is simply taken for granted. When Wade says that “religious truths are accepted not as mere statements of fact but as sacred truths, something that it would be morally wrong to doubt” (ibid., 164) this may have some relevance to modern religion, but it has none to the forms of religion in primitive society.

The other selective advantage of religion, according to Wade, is that “It was then co-opted by the rulers of settled societies as a way of solidifying their authority and justifying their privileged position” (ibid., 164). The cynical ruler, smirking behind his hand at the simplicity of the peasants who thought him divine, is actually an invention of the Enlightenment. In fact, in primitive society authority itself attracts sacred status, so that in the traditional society of the Tauade when a Big Man died his body would be put into a specially built enclosure which women were not allowed to enter. Pigs were then slaughtered inside the enclosure and the sacred bull-roarer was whirled, away from the gaze of the women. If enough boys were available they would be kept inside the enclosure in a little hut for several months where they could imbibe the vitality of the dead chief and were taught by adult men to be tough and aggressive. The Big Man’s corpse, meanwhile, had been put on a special platform in his hamlet where it was allowed to rot, and it was thought that people absorbed the powers of the Big Man in the smell. Big Men also had a special association with certain birds of prey and sacred oaks, and were believed to be essential for the general health and well being of the group. But these folk beliefs were certainly not “invented” by the Big Men to drum up support.

Again, among the Konso the head of the lineage, the poqalla , inherited large amounts of land and was generous to lineage members who needed it with land, stock, and grain, settled disputes between lineage members and represented them in disputes with other lineages. But he was also a sacred figure who was responsible for blessing the members of the lineage and performed annual ceremonies for their health and prosperity; his home was a temporary sanctuary for those who had killed someone; and he was forbidden to attend funerals or visit a home in mourning. Anyone who had been to a funeral had to purify themselves before entering the homestead of the poqalla . In some parts of Konso the poqalla was also not supposed to kill either in war or hunting, and when they died very special funerals were performed for them. There were also regional poqalla who had religious and peacemaking functions for groups of villages. In primitive society, then, authority attracts sacred status which, together with inherited office, is the basis of kingship in later societies.

Rulers and those in authority did not, then, in any meaningful sense of the word, “co-opt” religion to justify their privileged position. On the contrary, it was the general human disposition to attribute sacred status to those in authority that was one of the main reasons why it could develop.

(e) Homosexuality and gay uncles

A standing problem in evolutionary psychology is that if there is a substantial genetic basis for homosexuality then how could this have been retained by natural selection, which would inevitably weed out any such disposition to infertility. A classic solution was E.O. Wilson’s theory in his On Human Nature that homosexuals ‘could have’ increased their inclusive fitness in foraging bands by assisting their close relatives in child care:

The homosexual members of primitive societies could have helped members of the same sex, either while hunting and gathering or in more domestic occupations at the dwelling sites. Free from the special obligations of parental duties, they would have been in a position to operate with special efficiency in assisting close relatives. They might further have taken the roles of seers, shamans, artists, and keepers of tribal knowledge. If the relatives—sisters, brothers, nieces, nephews, and others—were benefited by higher survival and reproductive rates [my emphasis], the genes these individuals shared with the homosexual specialists would have increased at the expense of alternative genes. Inevitably, some of these genes would have been those that predisposed individuals toward homosexuality. (Wilson 1978: 145)

A study in Samoa purports to provide strong evidence for Wilson’s theory:

Androphilia refers to sexual attraction and arousal to adult males, whereas gynephilia refers to sexual attraction and arousal to adult females. Previous research has demonstrated that Samoan male androphiles (known locally as fa’afafine ) exhibit significantly higher altruistic tendencies toward nieces and nephews than do Samoan women and gynephilic men. The present study examined whether adaptive design features characterize the psychological mechanisms underlying fa’afafine ‘s elevated avuncular tendencies. The association between altruistic tendencies toward nieces and nephews and altruistic tendencies toward nonkin children was significantly weaker among fa’afafine than among Samoan women and gynephilic men. We argue that this cognitive dissociation would allow fa’afafine to allocate resources to nieces and nephews in a more economical, efficient, reliable, and precise manner. These findings are consistent with the kin selection hypothesis , which suggests that androphilic males have been selected over evolutionary time to act as ‘helpers-in-the-nest,’ caring for nieces and nephews and thereby increasing their own indirect fitness. (Vasey & Vanderlaan 2010)

In the first place, this study does not show that the nieces and nephews of the fa’afafine actually benefited from these resources from their uncles so that, as Wilson says, they achieved higher survival and reproductive rates than those without these uncles. Unless this were the case, the homosexual uncles could not have achieved any increase in their inclusive fitness. The Samoan fa’afafine is only a special case of what anthropologists know as the avunculate, where the mother’s brother has special responsibilities for his sister’s children. I actually demonstrated at length (Hallpike 1984) that these gifts of resources in the avunculate relationship were in fact purely ceremonial and could have no effective impact on the life chances of their recipients.

Moreover, the homosexual Samoan fa’afafine is a highly unusual institution, and in order to put it in context we need to look at marriage more generally in primitive society, and the first thing we notice is that especially among hunter-gatherers marriage is the norm for everybody. For example:

In Aboriginal Australia generally, the question of whether or not a person should marry does not arise. It is conventionally expected of everyone as a matter of course, and the main problem, who will be selected. A married man is fully, and unquestionably, an adult. Having children confirms his status, even in cases where that is not an acknowledged pre-requisite. And this is so for as woman as well. (Berndt & Berndt 1964: 166)

This is overwhelmingly the impression given by the literature on other hunter-gatherer societies, and indeed on tribal societies generally. Girls in particular seem always to be required to marry and may have their spouses selected for them, and the pressure on men is almost equal. I never encountered a woman either among the Konso or the Tauade who had not married, although one Konso woman had been rejected by her husband because she was barren. Among the Konso the only men who did not marry were the sakoota , who were clearly rather effeminate, wore skirts, practised female crafts and were thoroughly despised. They were a tiny proportion of the population, a fraction of one percent, and were a source of shame to their kin, certainly not benevolent gay uncles. Among the Tauade there was also a class of unmarried men, the “rubbish-men” who are a standard New Guinean institution like the Big Man. But I never heard any suggestion that they were homosexual, but were simply social inadequates that no woman would consider marrying. Indeed, when I asked my main informant Amo Lume about homosexuality he had to think hard before he recalled one man who had liked to wear a European dress after these began to be imported. But that was the only example he could think of, and I could find no references to homosexuality among the Tauade either in their myths or in local court cases or any of the patrol reports.

Ford and Beach (1951), in their cross-cultural survey of sexual practices and attitudes, report that of the seventy-six societies for which information was available for their survey, in twenty-eight of them homosexual activities between adults were either absent or very rare. In the remaining forty-nine, homosexual activities were acceptable for certain members of the community, and the commonest of these was similar to the Konso sakoota, or berdache as the role is commonly known, and might often be a shaman and ascribed magical powers:

Among the Siberian Chukchee such an individual puts on women’s clothing, assumes female mannerisms, and may become the “wife” of another man. The pair copulate per anum , the shaman always playing the feminine role. In addition to the shaman “wife”, the husband usually has another wife with whom he indulges in heterosexual coitus. The shaman in turn may support a feminine mistress; children are often born of such unions.(Ford & Beach 1951: 130-31)

But homosexuality in tribal societies most frequently involves adolescent boys, not gay uncles:

Among the Siwans of Africa, for example, all men and boys engage in anal intercourse. They adopt the feminine role only in strictly sexual situations and males are singled out as peculiar if they do not indulge in these homosexual activities (ibid., 131-32). Among many of the Aborigines of Australia this type of coitus is a recognized custom among unmarried men and uninitiated boys. Strehlow writes of the Aranda as follows: ‘Pederasty is a recognized custom…. Commonly a man, who is fully initiated but not yet married, takes a boy of ten or twelve years old, who lives with him as a wife for several years, until the older man marries’… Keraki bachelors of New Guinea universally practice sodomy, and in the course of his puberty rites each boy is initiated into anal intercourse by the older males. After his first year of playing the passive role he spends the rest of his bachelorhood sodomizing the newly initiated. This practice is believed by the natives to be necessary for the growing boy (ibid., 132). (In due course the boys marry in the usual way.)

Wilson’s hypothesis of the helpful, nepotistic homosexual uncle increasing his inclusive fitness by looking after his nieces and nephews does not, then, find any ethnographic support, and his ideas are in fact completely uninformed speculation. Even accepting that there are genes disposing people to homosexuality, Wilson’s basic fallacy is very simple: he assumes, quite wrongly, that homosexuals can’t (or won’t) marry and have children, whereas there is plenty of evidence from anthropology, the classical world, and more recent history, that homosexuals of both genders are quite capable, in most cases, of marrying and begetting children. Given the enormous social pressures for marriage in traditional societies, it is far simpler than Wilson’s scenario, and more in accordance with the known facts, merely to assume that if these genes for homosexuality exist, they were perpetuated by those with homosexual inclinations who nevertheless married and begot children, thereby making their “homosexual” genes invisible to natural selection.

Notes

Dunbar (1996)…claims a unique pressure for human ancestors [to develop language]: the growth of groups to a size too large to allow time for the grooming that forms a vital part of primate interactions. But other arguments render this implausible. There is no evidence that human groups grew larger than ape groups until quite recently, indeed what little evidence there is points in the opposite direction. Baboon groups are substantially larger than ape groups, yet no grooming substitute has developed among them. No valid reason is given for why meaningless, soothing sounds would not have functioned as well (or better) as a grooming device than a more complex adaptation that required every utterance to have some sort of propositional meaning. The sole function claimed by Dunbar—gossip—could not have been exercised until language acquired a critical mass of at least several hundred words, for in its earliest stages its symbols were presumably enumerable in the single digits, and how many items of gossip could you convey with a single set of nine words? For language to enter the repertoire of human behavior, it had to convey an adaptive advantage from its very earliest stages, or it would never have fixed.(Bickerton 2007: 514-15)

Chapter II: A response to Swearing is Good for You. The amazing science of bad language , by Emma Byrne

Ship of Fools

Ship of Fools