- Home

- C R Hallpike

Ship of Fools Page 14

Ship of Fools Read online

Page 14

[H]uman cognitive systems, when seriously investigated, prove to be no less marvellous and intricate than the physical structures that develop in the life of the organism. Why, then, should we not study the acquisition of a cognitive structure such as language more or less as we study some complex bodily organ? (Chomsky 1975: 10). What many linguists call ‘universal grammar’ may be regarded as a theory of innate mechanisms, an underlying biological matrix that provides a framework within which the growth of language proceeds. (Chomsky 1980a: 187)

For Chomsky the basic or defining element of the language organ is recursion, recursion not simply in the sense of iteration, repeating the same process indefinitely, but in the sense of taking the output of one stage in a process and making it the input of the next stage:

…lying at the heart of language: its capacity for limitless expressive power, captured by the notion of discrete infinity. …no species other than humans has a comparable capacity to recombine meaningful units into an unlimited variety of larger structures [my emphasis], each differing systematically in meaning. (Hauser, Chomsky & Fitch 2002: 1576)

Recursion, then, in this sense is the structure-building process par excellence , particularly the process linguists refer to as embedding, in which one clause is included or subordinated in another:

Natural languages go beyond purely local structure [e.g., phrases] by including a capacity for recursive embedding of phrases within phrases, which can lead to statistical regularities that are separated by an arbitrary number of words or phrases [e.g., in the sentence “The man whom you saw yesterday speaks French” the subject “man” is separated from the verb “speaks” by the four words of the relative clause]. Such long-distance, hierarchical relationships are found in all natural languages [my emphases]. (ibid., 1577)

Linguists have generally made a clear distinction between iteration and recursion, whose distinctive property is the embedding of phrases or sentences within larger phrases or sentences.

Unfortunately, Chomsky in the same paper also says that recursion “takes a finite set of elements and yields a potentially infinite array of discrete expressions” (ibid., 1571) and had previously substantially revised his notion of UG by reducing it to the fundamental principle of Merge. This simply “takes a pair of syntactic objects and replaces them by a new combined syntactic object” (Chomsky 1995: 226), and appears in fact to blur substantially the distinction between recursion and iteration. Bickerton (2009: 536-7) indeed claims that iteration in the form of Merge can achieve the same results as recursion in the traditional sense. Some linguists have even concluded that any expression of more than two words must involve recursion-as-iteration, which is singularly unhelpful. This is a debate that one must therefore leave to linguists; but the fact remains that the concept of recursion as requiring embedding, subordinate clauses, is an extremely important cognitive process that is highly relevant to the notion of linguistic complexity and is also testable:

[T]he core idea of recursion is clear and unambiguous, and it is the simplest and most powerful route to the type of unbounded expressive power that is a crucial feature of mathematics or language.… Recursive embedding of phrases within phrases is an important tool allowing language users to express any concept that can be conceived, to whatever degree of accuracy or abstraction is needed. The achievements of human science, philosophy, literature, law, and of culture in general depend, centrally, upon there being no limit to how specific (or how general) the referents of our linguistic utterances can be. (Fitch 2010: 89)

For the purposes of this paper I shall therefore ignore the implications of Merge, and concentrate on the theory that language is genetically based in a “language organ”, and that its most important manifestation is recursive embedding.

But, unlike the earlier descriptivist linguists like Boas and Sapir, who made intensive field-studies of the languages of the Native Peoples of North America, Chomsky based his theories essentially on English. He defended this as follows:

I have not hesitated to propose a general principle of linguistic structure on the basis of observation of a single language. The inference is legitimate, on the assumption that humans are not specifically adapted to learn one rather than another human language, say English rather than Japanese. Assuming that the genetically determined language faculty is a common human possession, we may conclude that a principle of language is universal if we are led to postulate it as a ‘precondition’ for the acquisition of a single language. (Chomsky 1980b: 48)

In rather the same way, perhaps, Newtonian physics might defend itself by saying that although it was based on the study of only one solar system, the laws inferred from this were universal. But in the course of time it became clear that languages from non-literate peoples in particular departed in major ways from this English-derived model, and the language organ now includes what have come to be known as “Principles and Parameters”. “Principles” are the universals of language, whereas “Parameters” respond to linguistic differences : they are the fundamental options or possibilities in generating the grammar of a language: “…also specified are the relevant principles and parameters common to the species and part of the initial state of the organism; these principles and parameters make up part of the theory of grammar or Universal Grammar, and they belong to the genotype” (Anderson and Lightfoot 2000: 14). One parameter, for example, is word order, and it seems that 95% of the world’s languages are either SVO, like English, or SOV like German. Another is the “Null-Subject” parameter: with English verbs it is not permissible to omit the subject and say simply “is raining”: the form “it is raining” is required, even though “it” has a purely grammatical function here. In Italian, however, the form “piove ”, “is raining” is quite correct, and this null-subject parameter also explains a number of other related aspects of the grammars of English and Italian, and many other languages (Baker 2001: 36-44) ⁴ .

So we now find very strong claims for the scope of the “language organ”, for example:

All languages have a vocabulary in the thousands or tens of thousands, sorted into part-of-speech categories including noun and verb. Words are organized into phrases according to the X-bar system (nouns are found inside N-bars, which are found inside noun phrases, and so on). The higher levels of phrase structure include auxiliaries … which signify tense, modality, aspect, and negation. Nouns are marked for case and assigned semantic roles by the mental dictionary entry of the verb or other predicate. Phrases can be moved from their deep structure positions, leaving a gap or “trace”, by a structure-dependent movement rule, thereby forming questions, relative clauses, passives, and other widespread constructions. New word structures can be created and modified by derivational and inflectional rules. Inflectional rules primarily mark nouns for case and number, and mark verbs for tense, aspect, mood, voice, negation, and agreement with subjects and objects in number, gender, and person. (Pinker 2015: 235-6)

And some linguists make equally strong claims for the scope of a genetic basis of language: “Much remains to be done, but …[e]ventually, the growth of language in a child will be viewed as similar to the growth of hair: just as hair emerges with a certain level of light, air, and protein, so, too, a biologically regulated language organ necessarily emerges under exposure to a random speech community” (Anderson and Lightfoot 2000: 21).

Finally, we need to consider Chomsky’s explanation for how such a genetically based “language organ” could have developed in the first place. Strikingly, unlike Pinker and many others, he does not believe that it was the product of natural selection at all. This is because he also dismisses the general assumption that the origins of language must have been in the context of communication , that, if you like, there is no point in speaking if there is no one else who can understand what is being said. He maintains that the “language organ” resulted from a major genetic mutation, probably within the last 100,000 years:

Within some small group from which we are de

scended, a rewiring of the brain took place in some individual, call him Prometheus, yielding the operation of unbounded Merge, applying to concepts with intricate (and little understood) properties.… Prometheus’s language provides him with an intricate array of structured expressions with interpretations of the kind illustrated: duality of semantics, operator-variable constructions…. Prometheus had many advantages: capacities for complex thought, planning, interpretation, and so on. The capacity would then be transmitted to offspring, coming to predominate…. At that stage there would be an advantage to externalization, so the capacity might come to be linked as a secondary process to the S[ensory]M[otor] system, for externalization and interaction, including communication [through speech]. (Chomsky 2010: 59)

Prometheus’s mutation, in other words, initially applied only to Inner thought, Mentalese, I[nternal]-Language, not to E[xternal]-Language or real speech. This refers to the fact that there has to be a distinction between thoughts and words: we are all aware, for example, of searching for just the right word to express an idea we have, of feeling we have not expressed our meaning very well, of objecting to someone’s theory before we have actually put our objection into words, and so on. But it is not in the least obvious how this mutation could have conferred any capacity for “complex thought” in the absence of any social interaction, or any language in which to exchange these thoughts. Chomsky nevertheless maintains that the mutation in question was about our increased ability to think with precision, not to communicate any better, and that this in itself would have been of sufficient adaptive advantage to Prometheus to ensure the propagation of the language gene:

Salvador Luria was the most forceful advocate of the view that communicative needs would not have provided ‘any great selective pressure to produce a system such as language,’ with its crucial relation to ‘the development of abstract or productive thinking.’ The same idea was taken up by his fellow Nobel laureate François Jacob, who suggested that ‘the role of language as a communication system between individuals would have come about only secondarily, as many linguists believe.… The quality of language that makes it unique does not seem to be so much its role in communicating directives for action’ or other common features of animal communication, but rather ‘its role in symbolizing, in evoking cognitive images’, in ‘molding’ our notion of reality and yielding our capacity for thought and planning, through its unique property of allowing ‘infinite combinations of symbols’ and therefore ‘mental creation of possible worlds’. (Chomsky 2010: 55)

4. Is a “language organ” actually possible?

There are, unsurprisingly, a number of objections to this view of the language organ and U[niversal] G[rammar]. (As previously mentioned, this is now referred to as the Minimalist principle of unbounded Merge but for simplicity I shall continue to refer to UG.) The first is that it is bizarre to claim that language can be a physical organ in the same sense as the heart or the eye. These have standard forms and functions, which are genetically determined and entirely material in nature, and are also confined to the operation of the body of which they are parts. Language, on the other hand, although having some kind of genetic basis is also, unlike the bodily organs, a social phenomenon produced by the interaction of many minds, and is also concerned with the communication of non-material meaning between a number of individuals. Like the brain of which it is one function among many, but unlike all the other bodily organs, it is capable of limitless diversity, and it can also develop very different levels of complexity, again unlike all other bodily organs. The idea that language is an organ like the heart or the eye is therefore vastly underdetermined by the evidence.

The next objection is that, when faced with Chomsky’s mythical Prometheus, whose ability to master the most complex syntax suddenly appeared fully formed in his brain, we need to remind ourselves of a basic principle of natural selection. This is that a trait can only be selected if it is relevant to the existing circumstances in which an organism is living, not those that might exist in the future. This point was made long ago by A.R. Wallace, the co-formulator of the theory of natural selection with Darwin, and who had extensive first-hand acquaintance with hunter-gatherers of the Amazon and south-east Asia. He noted that on the one hand their mode of life made only very limited intellectual demands, and did not require abstract concepts of number and geometry, space, time, and advanced ethical principles, or music, yet they were potentially capable of mastering the advanced cognitive skills of modern industrial civilisation. Since natural selection can only produce traits that are adapted to existing, and not future, conditions, it “could only have endowed savage man with a brain a little superior to that of an ape, where he actually possesses one little inferior to that of a philosopher” (Wallace 1871: 356). But how could the language organ have developed the capacity for the highly complex syntactic structures involved in, say, modern legal or philosophical arguments tens of thousands of years before they were needed or relevant to the simple lives of hunter-gatherers?

Chomsky, of course, would dismiss Wallace’s point on the grounds that the linguistic ability of Prometheus was not produced by natural selection at all, but by an amazing mutation instead. This escape of Prometheus from what might seem an impossible evolutionary situation is about as implausible as the legendary escape of Jack, the hero of a thriller series, from apparently inevitable death by the explanation that “with one bound Jack was free”. Evolutionary psychologists such as Pinker naturally disagree fundamentally with Chomsky and maintain that communication was basic, and that language is only one of a large number of “modules” in the brain that have evolved over millions of years through natural selection. According to Pinker, “The mind is organized into modules or mental organs, each with a specialized design that makes it an expert in one arena of interaction with the world. The modules” basic logic is specified by our genetic program” (Pinker 1997: 21), and language is just one module among very many. These modules are supposed to have been shaped by natural selection during the several million years of hunter-gatherer life the Pleistocene in East Africa, the “environment of evolutionary adaptation” or EEA (about which, incidentally, we know virtually nothing). So:

Just as one can now flip open Gray’s Anatomy to any page and find an intricately detailed depiction of some part of our evolved species-typical morphology, we anticipate that in 50 or 100 years one will be able to pick up an equivalent work for psychology and find in it detailed information-processing descriptions of the multitude of evolved species-typical adaptations of the human mind, including how they are mapped on to the corresponding neuro-anatomy and how they are constructed by developmental programs. (Tooby and Cosmides 1992: 69)

Mathematics is another of these alleged modules, and its comparison with the language “organ” is illuminating here. Unlike language, which is both universal and very ancient, mathematics much beyond the level of simple tallying only emerged in the high cultures of recorded history, and its expert practitioners have always been a small minority of any population. According to Pinker, “Mathematics is part of our birthright” (1997: 338), but this is only true in a very rudimentary sense. When collections of objects are less than ten, a wide variety of species such as pigeons, ravens, parrots, rats, monkeys, and chimpanzees can recognise changes in the numbers of objects in a collection, compare the sizes of two collections presented simultaneously, and remember the number of objects presented successively (Koehler 1951, Pepperberg 1987, Mechner & Guerrekian 1962, Woodruff & Premack 1981, Matsuzawa 1985).

A sense of what has been called “numerosity”, then, of the differences in quantities of small size, is widespread, and to this extent the human “mathematical birthright” is not distinguishable from that of many other species. So many simple cultures, especially hunter-gatherers but including some shifting cultivators such as the Tauade of Papua New Guinea (Hallpike 1977), may only have words for single, pair, and many. Indeed, the hunter-gatherer Piraha of South America are described by

Everett (2008) as having no number words at all, not even the grammatical distinction between singular and plural, but we shall come back to them in more detail later.

We can get a good idea why this should be so from the example of a Cree hunter from eastern Canada: he was asked in a court case involving land how many rivers there were in his hunting territory, and did not know:

The hunter knew every river in his territory individually and therefore had no need to know how many there were. Indeed, he would know each stretch of each river as an individual thing and therefore had no need to know in numerical terms how long the rivers were. The point of the story is that we count things when we are ignorant of their individual identity [my emphasis]—this can arise when we don’t have enough experience of the objects, when there are too many of them to know individually, or when they are all the same, none of which conditions obtain very often for a hunter. If he has several knives they will be known individually by their different sizes, shapes, and specialized uses. If he has several pairs of moccasins they will be worn to different degrees, having been made at different times, and may be of different materials and design. (Denny 1986: 133)

Again, the Tauade, like many peoples of Papua New Guinea, only had words for single, kone , and pair, kupariai. “Single” and “pair”, it should be emphasized, are not the same as one and two: 2 is 1+1, and 3 is 1+1+1, successive elements of a series, but “single” and “pair” are not components of a series but are configurations that can take many different forms. For example there are pairs of twins, or a man and a woman, a man and a man, and a woman and a woman, or left and right, or sun and moon, and so on which each have different social and symbolic significance, whereas there can’t be different kinds of 1 or 2. Although the Tauade engage in complex transactions of pork exchange they have never needed to use a counting system to keep track of these because each exchange is unique, between different persons, for different purposes and in different circumstances. Here again, like the Cree, distinctive individual identity is key to the lack of number and counting. (The Tauade had only recently adopted the Tok Pisin number system based on ten because they had to deal with modern money whose coins and notes have no individual identity.) What needs to be emphasised here, therefore, is that in hunter-gatherer societies especially, it is perfectly possible to survive without the need for verbal numerals or for counting, and that consequently there could have been no selective pressure for arithmetical skills to evolve in the specific conditions of the EEA, and for any specific module to develop. So are we really expected to believe that a mathematics module, with all its capacity to produce modern mathematics, nevertheless did develop but mysteriously sat there in silence, as it were, until the emergence of complex societies?

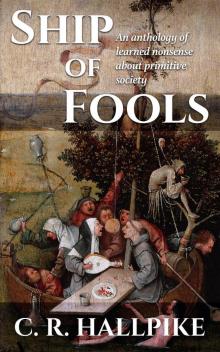

Ship of Fools

Ship of Fools