- Home

- C R Hallpike

Ship of Fools Page 12

Ship of Fools Read online

Page 12

Not all cannibalism, by any means, was so bound up in the culture’s religious and social life, and could be quite perfunctory. Mr William Mariner was a young captain’s clerk who was captured by the Tongans in 1806 when they seized his ship and killed most of the crew. He became a favourite of King Finow, learnt the language, and was a close and very intelligent observer of Tongan life until he managed to escape in 1810. (On his return to London he was befriended by a physician, Dr John Martin, who published an account of his experiences.) During one of the many wars in which Mariner was involved he made the following observation on cannibalism:

The following day, some of the younger chiefs, who had contracted the Fiji habits [my emphasis] proposed to kill the prisoners, lest they should make their escape, and then to roast and eat them. The proposal was readily agreed to, by some, because they liked this sort of diet, and by others because they wanted to try it, thinking it a manly and warlike habit. There was also another motive, viz. A great scarcity of provisions; for some canoes which had been sent to the Hapai islands for a supply were unaccountably detained, and the garrison was already threatened with distress. Some of the prisoners were soon despatched; their flesh was cut up into small portions, washed with sea-water, wrapped up in plantain leaves, and roasted under hot stones; two or three were embowelled, and baked whole the same as a pig. (Martin 1827(I): 107-8)

Mariner notes that “When Captain Cook visited these islands, cannibalism was scarcely thought of amongst them, but the Fiji people soon taught them this, as well as the art of war” (ibid., 108-9).

Mariner also witnessed a second instance of cannibalism. Sixty men had been killed in a siege of fortress by King Finow, and after they had been dedicated to various local gods, the nine or ten bodies belonging to the enemy:

…were conveyed to the waterside, and there disposed of in different ways. Two or three were hung up on a tree; a couple were burnt; three were cut open from motives of curiosity, to see whether their insides were sound and entire [the liver of those guilty of sacrilege was supposed to become diseased], and to practise surgical operations upon, hereafter to be described; and lastly, two or three were cut up to be cooked and eaten, of which about forty men partook. This was the second instance of cannibalism that Mr Mariner had witnessed; but the natives of these islands are not to be called cannibals on this account. So far from its being a general practice, when these men returned to Neafoo after their inhuman repast, most persons who knew it, particularly women, avoided them, saying Iá-whé moe ky-tangata , ‘Away! You are a man-eater’. (ibid., 172-73)

Despite the initial circumstances of his capture, Mariner established very friendly relations with the Tongans, whom he clearly liked, and was an intelligent, well-qualified and fair-minded observer. Modern anthropologists are quite justified in accepting his evidence, particularly as it is supported by many other observers of the period.

Another good test of Arens’s scholarship is his analysis of accounts of cannibalism in South America, of which a book published in 1557 by Hans Staden, a sixteenth-century German sailor, is given close attention:

Hans Staden [was] an extraordinary fellow who visited the South American coast in the mid-sixteenth century as a common seaman on a Portuguese trading ship. Through a series of misfortunes, including shipwreck, he was soon captured by the Tupinamba Indians. As a result of his ill luck, the Tupinamba have come down to us today as man-eaters par excellence. (22)

Arens’s most serious charge against Staden is that he had little or no command of the Tupi language which, if true, would completely discredit his account of them:

There are also the matters of language and ability to recollect to be considered. In one instance, the narrator ruefully mentions being unable to communicate his plight to a Frenchman who visited his captors” settlement. Apparently he had no facility in the language of his fellow European. However, Staden is able to provide the details of numerous conversations among the Indians themselves, even though he was with them for a relatively limited period. He is particularly adept at recounting verbatim the Indian dialogue on the very first day of his captivity, as they discussed among themselves how, when, and where they would eat Staden. Obviously, he could not have understood the language at the time, and was reconstructing the scene as he imagined it nine years before. The later dialogues in the text must also have been a reconstruction, since there is no indication he kept notes, even if he could write. In one scene, which stands as a testimony to Staden’s memory and piety, he repeats the psalm “Out of the deep have I cried unto thee.” The Indians respond: “See how he cries; now he is sorrowful indeed”(67). One would have to assume that the Indians also had a flair for languages in order to understand and respond to Staden’s German so quickly. In summary, there was great opportunity for a certain degree of embellishment by the author, as well as by his colleagues in the eventual publishing venture. (25-6)

Donald Forsyth, a leading authority on Brazilian ethnohistory, comments:

Arens’s implication (1979: 25) that, because Staden couldn’t speak the language of his “fellow European”, he couldn’t speak Tupi either, makes about as much sense as arguing that because an individual has no facility in Russian, he couldn’t possibly have any in Portuguese either.” (Forsyth 1985: 21)

It is actually obvious from Staden’s own account that he understood Tupi perfectly well from the beginning:

For example, on the very day of his capture he explained (Staden 1928: 65): ‘The savages asked me whether their enemies the Tuppin Ikins had been there that year to take the birds during the nesting season. I told them [emphasis added] that the Tuppin Ikins had been there, but they proposed to visit the island to see for themselves….’ If Staden did not speak Tupi at the time of his capture, then there is no way that he could have told them anything, since it is hardly likely that his captors spoke German or Portuguese. (ibid., 21)

It is in fact very probable that Staden had learnt Tupi well before his capture, since he had lived on the coast of Brazil for two years with a number of other Europeans before he fell into the hands of the Tupinamba. During this time there was constant contact with local Indians who spoke the Tupi language, which was common to a number of tribes besides the Tupinamba. As Forsyth says, “Tupi was the lingua franca of Brazil at this time (and for a long time to come). The Europeans learned to speak Tupi, rather than the Tupians learning French or Portuguese” (ibid., 22-3). After a year Staden and other Europeans reached the Portuguese settlement of Sao Vicente. He worked for the Portuguese for a year, during which he was given a Tupi-speaking slave who worked for him on a daily basis, giving him ample opportunity in itself to learn the language.

Arens is also entirely mistaken when he claims that the Tupi would have had to understand German when responding to Staden’s singing of a psalm:

[T]his is simply not so. Staden (1928: 67) actually says: “So in mighty fear and terror I bethought me of matters which I had never dwelt upon before, and considered with myself how dark is the vale of sorrows in which we have our being. Then, weeping , I began in the bitterness of my heart to sing the Psalm: ‘Out of the depths have I cried unto thee.’ Whereupon the savages rejoiced and said: ‘See how he cries : Now he is sorrowful indeed’ [emphasis added]”. It is not to the German words of the psalm that the Indians respond, rather to the fact that Staden was weeping. (Forsyth 1985: 23-4)

Arens also refers to:

…a small paragraph which curiously informs the reader that ‘the savages have not the art of counting beyond five’. Consequently, they often have to resort to their fingers and toes. In those instances when higher mathematics are involved extra hands and feet are called in to assist in the enumeration. What the author is attempting to convey in his simple way with this addendum is that the Tupinamba lack culture in the sense of basic intellectual abilities. The inability to count is to him supportive documentation for the idea that these savages would resort to cannibalism. To Staden and many others, eating human fles

h implies an animal nature which would be accompanied by the absence of other traits of “real” human beings who have a monopoly on culture. (Arens 1979: 23-4)

Chagnon (1977: 74) states that the Yanomamo only have words for one and two, and I record that the same is true of the Tauade; neither of us, however, was trying to insinuate that the Yanomamo and the Tauade were therefore subhuman animals, and Forsyth adds that “Arens completely ignores the fact that Staden’s statement concerning Tupinamba enumeration is correct. Ancient Tupi had no terms for numbers beyond four. Larger numbers were expressed in circumlocutions, often involving fingers and toes” (Forsyth 1985: 19). If Arens were better informed he would know that very restricted number systems are often found among hunter-gatherers and simple cultivators, and this condescending, ad hominem attack on Staden tells us much more about Arens’s prejudices than about Staden’s.

Finally, Arens tries to argue that later authors who at first sight appear to confirm Staden’s account of cannibalistic ceremonies were in fact simply plagiarising him. Forsyth, however, dismisses the claim of plagiarism entirely:

Arens’s (1979: 28-30) whole argument is based on the similarities in the accounts of Staden, Lery (1974: 196), Thevet (1971: 61-63), Knivet (1906: 222), and Casas (1971: 68) with respect to the verbal exchange between the victim and executioner before an enemy was killed, cooked, and eaten. His argument is as follows:

In his chapter on killing and eating the victim, Staden supplies some further Indian dialogue which he translates for his readers. He states that the Indian who is about to slay the prisoner says to him: ‘I am he that will kill you, since you and yours have slain and eaten many of my friends.’ The prisoner replies: ‘When I am dead I shall still have many to avenge my death’ [Staden 1928: 161]. Dismissing the linguistic barrier momentarily, … the presentation of the actual words of the characters lends an aura of authenticity to the events. However, if similar phrases begin make their appearance in the accounts of others who put themselves forward eyewitnesses to similar deeds, then the credibility of the confirmation process diminishes (Arens 1979: 28-29). Arens cites the other authors to show the similar phraseology used in describing the execution scene. Hence his whole case for plagiarism is similarities in two sentences in works that are book length in most instances (see Riviere 1980: 204).

As it turns out, however, when even these two sentences are examined in the context of what we know about the cannibalistic rites themselves, and about how and when the accounts were produced, Arens’s argument evaporates. An example from our own literate society should suffice to show why this is so. If several different observers wrote a description of the Pledge of Allegiance ceremony, which takes place daily in schools all over the nation, we should hardly be surprised to find considerable similarity, since what is said is an essential element in the ceremony. But according to Arens’s logic, we would have to conclude that the writers were all copying one another. But the Pledge of Allegiance is not a random event in the daily activities of American school-children. It is, rather, a ritual charged with symbolic meaning. In such a ritual the repetition of behavior and utterance is an integral part of the ceremony.… The verbal exchanges cited by Arens between executioner and victim were not simply random babblings, but highly ritualized exchanges constrained by custom and belief at the very climax of the ceremony, as virtually all of the accounts make patently clear. (Forsyth 1985: 27-8)

Forsyth also points out that Arens ignores a wealth of Jesuit sources that provide eyewitness accounts of cannibalism, the confiscation of cooked (and preserved) human flesh from the Indians, so that they would not eat it, the confiscation of bodies from Indians who were about to eat them, or persuading them to bury the bodies rather than eating them, in one case after the body was already roasted, and the successful rescue of prisoners before they could be killed and eaten:

Whatever the reliability of the better-known sources may be, the Jesuit sources are unimpeachable in this matter, because they avoid all of the alleged weaknesses of the accounts referred to by Arens. They are not copies of Staden, Lery, or Thevet; many of the letters and reports were written before these authors even arrived in Brazil. Moreover, many of the Jesuits did speak the Tupi tongue, even writing dictionaries and grammars to help others learn the language, and lived in Indian villages for extended periods of time. In addition, details of the various Jesuit accounts often differ sufficiently from one another to rule out plagiarism. (Forsyth 1983: 171)

Just as Forsyth claims that Arens ignores a wide range of original sources, particularly those of the Jesuits, Neil Whitehead (1984) also documents Arens’s similar failure to consult Jesuit sources with regard to the separate issue of Carib cannibalism.

So far, we have been considering accounts of cannibalism that involve the eating of enemy prisoners, usually killed or captured in warfare. Cross-culturally this appears to be the basic form of cannibalism; there seems little evidence that shortage of protein had anything to do with it, as materialists like Marvin Harris supposed; and many primitive societies were as strongly opposed to cannibalism as we are. There is, however, a different type of cannibalism, conventionally known as “endo-cannibalism”, in which the relatives of a deceased person eat the corpse, or part of it, as a mortuary rite. Roy Wagner gives a detailed account of this among the Daribi of the New Guinea Highlands (1967: 145-7), and to a very limited extent the Tauade also practised this:

When a person died and his body had rotted in the tseetsi [a raised basket] or in the ground, the bones were taken by his relatives and washed in a stream. The skull in particular was washed out with water introduced through the foramen magnum , with which the remains of the brain were flushed away. The children of the deceased are said to have drunk this water. (Hallpike 1977: 158)

Arens, however, is obliged to be just as dismissive of endo-cannibalism as he is of cannibalism in general, and occupies many pages in particular trying to discredit the accounts of this practice among the Fore of New Guinea, which became world-famous through its association with two Nobel Prize winners. Most people would probably consider the Fore case a major obstacle to his theory, and Arens’s attempts to dismiss it are excellent examples of the quality of his research. Patrol reports in the Fore area from the early 1950s onwards began describing a disease that became known as kuru . Its symptoms were trembling, difficulty in walking and co-ordination, mood changes, and slurred speech, leading to unconsciousness and death usually within a year or less from the first symptoms appearing. (The word kuru itself referred to the casuarina tree, whose quivering leaves were seen by the Fore as similar to that of the victims’ limbs.) The American physician Carleton Gajdusek happened to be in the area and was told about the disease by Dr Vincent Zigas. The anthropologist Ronald Berndt had already studied it, and considered it psycho-somatic, but Gajdusek came to the firm conclusion that it was entirely physical in origin, and in 1957 Gajdusek and Zigas published a paper claiming that it was a newly discovered neurological disease.

Initially it had been supposed that it might be genetic in origin, but this would have required a long evolutionary history and resulted in epidemiological equilibrium, whereas the Fore claimed that it had first appeared around the beginning of the century, thirty years before contact with Europeans, and its incidence had steadily increased throughout the 1940s and 1950s and was now killing very significant numbers of people. The mortality rate in some villages was 35/1000 per annum, and far more women than men were affected (Lipersky 2013: 479). In 1957, for example, approximately 170 women died compared to 35 men (ibid., Fig. 4, 476). In 1961 the anthropologists Robert and Shirley Glasse (later Lindenbaum) carried out fieldwork on the Fore, with the specific purpose of seeing if victims were close relatives, as the genetic hypothesis predicted, but discovered that they were not. They also made special enquiries into the endo-cannibalistic practices of the Fore, which had been suppressed some years before their work. In the late 1930s and 1940s, many gold miners, Protestant missionaries, and gover

nment officials (in other words, Arens’s usual “basket of deplorables” in this scenario), had already become familiar with the presence of endo-cannibalism among Eastern Highland tribes (Lipersky 2013: 475). The Glasses made their own enquiries from informants and were able to reconstruct the ways in which this had been carried out on the body of a deceased relative:

When a body was considered for human consumption, none of it was discarded except the bitter gall bladder. In the deceased’s old sugarcane garden, maternal kin dismembered the corpse with a bamboo knife and stone axe. They first removed hands and feet, then cut open the arms and legs to strip the muscles. Opening the chest and belly, they avoided rupturing the gall bladder, whose bitter content would ruin the meat. After severing the head, they fractured the skull to remove the brain. Meat, viscera, and brain were all eaten. Marrow was sucked from cracked bones, and sometimes the pulverized bones themselves were cooked and eaten with green vegetables. In North Fore but not in the South, the corpse was buried for several days, then exhumed and eaten when the flesh had ‘ripened’ and the maggots could be cooked as a separate delicacy. (Lindenbaum 2013: 224)

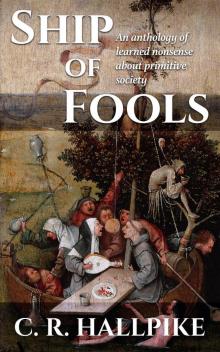

Ship of Fools

Ship of Fools